Detecting Invasive Leafminers from Space

Emily Graham

Foliage damage from birch leafminer infestations in central Alaska is rapidly escalating in a state known for its verdant forests and vibrant fall colors (USFS, 2008). Tracking these infestations is critical for managing forest health, but traditional methods for mapping the foliage damage characteristic of a leafminer infestation, such as aerial and pedestrian surveys, are cumbersome, expensive, and are not suitable for mapping large areas (Hall et al, 2016). They are also heavily dependent on weather conditions and a short seasonal window for data collection.

The Forest Service conducts the yearly mid-August Aerial Detection Survey in the Fairbanks area to map current birch leafminer infestation status, but wildfire activity prevented the 2023 survey (USFS, 2023). The Forest Service is one of the leading sources of forest health data in the state, but no data exists for that season. Imagine if we had a more accurate way to map infestations that could be done any time of the year and only required a computer with an internet connection?

Late Birch Leaf Edgeminer larva feeding inside a birch leaf leaf. Credit: USFS.

Here we will introduce a remote sensing approach to mapping birch leafminer infestations that starts with data collected in the field and steps through an novel workflow designed to detect leafminer infestations in birch forests quickly and cheaply by combining the power of statistics with planetary-scale optical imagery and freely available big geospatial datasets- all from the comfort of a single internet-connected computer. The goal of this project is to offer a reliable and accurate alternative to the cumbersome traditional infestation mapping methods still in use today. Early results of the analysis successfully classified study site pixel as potentially infested or not infested and show infestation density substantially increasing during the seasonal infestation peak.

Alaska’s uninvited guests

In the early 90’s two species of birch leaf-mining palearctic sawflies, a type of stingless wasp, arrived in Alaska, possibly hitching a ride on ornamental birch trees imported from Europe (Snyder et al., 2007). Since then, birch leafminer infestations have produced a staggering amount of damage to birch stands in Alaska and Canada, particularly focused around population centers. Over 90% of a tree’s leaves may be affected, which can disrupt its ability to conduct photosynthesis, weakening the trees and raising a number of concerns for forest health (USFS, 2023).

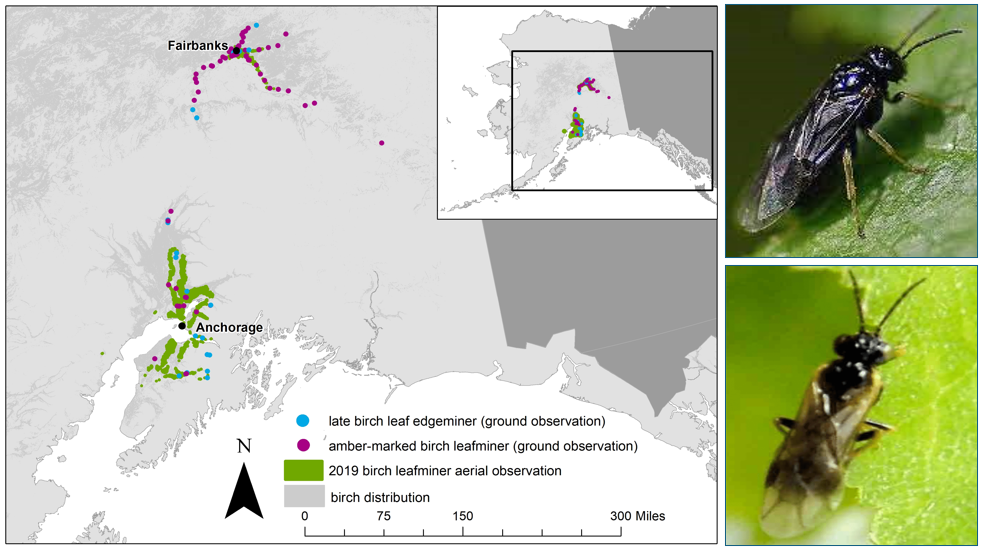

Map of 2019 infestation locations (left) and Amber-Marked Leafminer (top-right) and Late Birch Leaf Edgeminer (bottom right) adults. Credit: USFS.

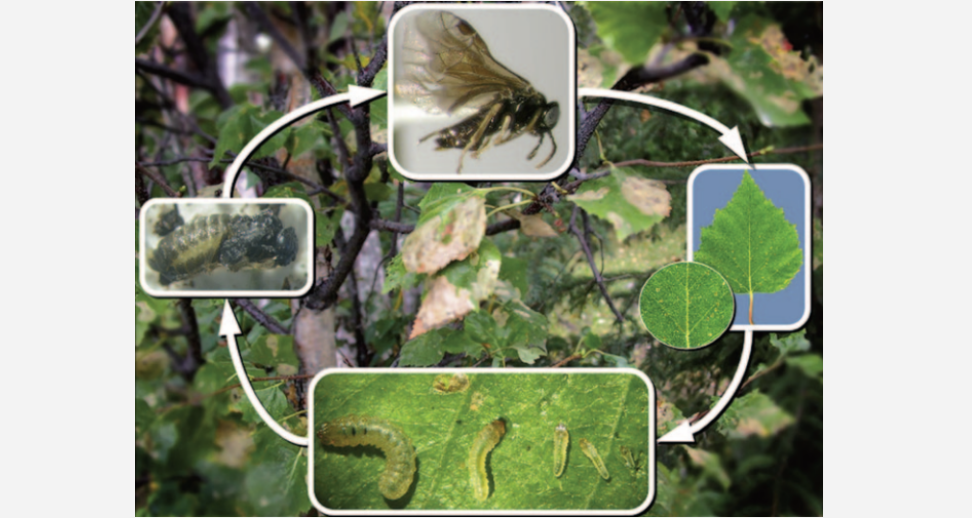

Alaska has two extant leafminer species, the Amber-Marked Birch Leafminer and the Late Birch Leaf Edgeminer. Both operate on the same overall business model- adults emerge in mid to late summer to lay eggs in birch leaves, which then hatch into larvae that make themselves at home within the leaf itself. They feed on the inner mesophyll layer, creating the characteristic leaf damage (mines). Larvae develop over an approximately 24-day period, after which they drop to the ground, pupate, and emerge as adults the following spring (Snyder et al., 2007). Successful control methods have been developed, but infestations persist, particularly in interior Alaska.

Birch leafminer life cycle. Credit: Snyder et al., 2007

In recent years, infestation patterns have been changing, possibly catalyzed by climate warming. Leafminer damage has been noted earlier in the season than previous years and infestations have been observed moving into more remote areas (USFS, 2019). Tracking these infestations as they grow and change is critical for implementing control measures and developing mitigation plans.

Leveraging leafminer behavior patterns to detect infestations

The existing literature has surprisingly few studies that mention using a remote sensing approach to map the birch leafminer problem. The Forest Service has investigated the use of remote sensing for Kenai Peninsula infestations (USDA, 2019), but there is no subsequent mention of this effort and they still rely on yearly aerial surveys.

Multispectral remote sensing analysis enables the detection of critical indicators such as chlorophyll and leaf moisture content, vegetation health, and the unique spectral signatures specific to foliage damage from infestations. Employing an approach that takes advantage of the dependable progression of the leafminer life cycle, their strict preference for birch hosts, and tendency to prefer populated areas offers a unique opportunity to develop a detection method capable of differentiating mining damage from senescence, water stress, and other pests or disease factors .

Building a method: from fieldwork to space to forest

Because traditional infestation mapping methods only offer generalized boundaries, few practical maps are available to the entities charged with forest management and policy development. Building a scientifically sound and reproducible method to create these maps is critical for decision-makers as they must stand behind the policies they make.

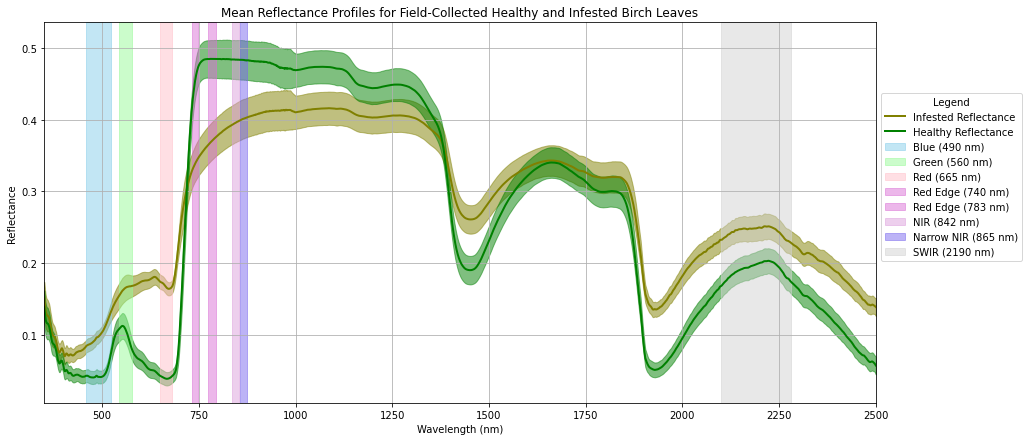

Our approach begins with raw spectral reflectance measurements collected in late summer 2023 from healthy and infested birch trees in Fairbanks, Alaska. Reflectance values for the field data’s 2500 wavelengths were processed in Python and a Cohen’s d statistical analysis applied to determine at which wavelengths the differences between healthy and infested measurements were statistically significant (p<0.05). The significant wavelengths were then grouped and aggregated to select the most useful Sentinel-2 bands for the analysis. The standard deviation range rule was applied to the infested reflectance values to create a threshold range for each band. If a pixel’s value fell into the assigned value ranges that indicated possible infestation for 80% of the bands tested, then it was marked as infested. If not, the pixel was marked as not infested.

Comparison of infested and healthy leaf reflectance values and statistically significant Sentinel-2 bands.

Next, we turn from Python to Google Earth Engine (GEE), a powerful cloud-based platform that empowers us to apply analyses across vast extents of geospatial data. First, GEE loaded high resolution Sentinel-2 optical images selected from early summer (pre-seasonal damage) and late summer (evident damage, but before fall colors set in), then applied the standard masks and corrections.

Fifteen birch stands in and around Fairbanks were selected from the Alaska Department of Natural Resources (DNR) 2023 Timber Inventory to become study site locations and their boundaries loaded into GEE. Each pixel within the site locations was tested using a majority threshold method that classified the pixel as infested if its reflectance values fell into the threshold ranges for 80% of the significant bands.

The early results of our analysis are interesting. Birch leafminers are known to prefer populated areas, as seen in the 2019 infestation points in the Forest Service map above. Sites 11 and 6 were selected for their close proximity to town and their location along busy roads. The classification results show a sizeable increase in potentially infested pixels from early to late summer.

Sites 11 (left) and 6 (right) are birch forest stands close to the town of Fairbanks urban structures.

In contrast, Site 2 is located farther away from town and does not directly interact with the road system. While it does have an increase in potentially infested pixels, this remote site has experienced notably less damage comparatively through the active summer infestation period.

Site 2 is located farther away from Fairbanks proper.

As expected, all fifteen study sites showed some level of possible infestations. Images captured in mid-May before trees really experience infestation damage had only a few pixels classified as infested. In contrast, study site pixels captured in late August when birch trees experience peak damage had substantially higher numbers of infested pixels across all locations.

The percentage of infested pixels varied somewhat across the analysis. Sites closest to town had the highest ratios of pixels classified as infested vs not-infested, which aligns with current understanding of infestation behavior patterns.

Limitations and considerations

While our leafmining friends are predictable, they do have some habits that create complications for mapping the results of their dining activities. A satellite sensor can most easily see the tops of trees, but leafminers tend to infest the sides of trees. The birch trees also add complications by growing as individual trees, mixed with other tree species, and as cohesive stands.

A major limitation of this novel method is the reliance on birch-only forest boundaries to build and test the model. Alaska DNR is an unquestionably authoritative source and working with areas known to be mostly birch species reduces noise in the data. Like the trees, birch leafminers do not constrain themselves only to birch forests. The model will need further development to work across pixels representing varied land covers.

Limitations aside, the overarching consideration for this project is refining a model whose results can be consistently proven to differentiate birch leafminer infestations from other sources of vegetation stress. Achieving this will involve careful refinement of the model, its threshold ranges, and testing it across additional field data and optical imagery datasets.

What’s next?

This analysis represents a new foray into reliably detecting and tracking birch leafminer damage using large-scale, freely available optical imagery datasets. The workflow from statistical analyses of field datasets to classifying study site pixels is an entirely new method that will require adjusting and additional assessments to ensure its reliability and accuracy.

The next important step is to acquire field measurements from sites across a wide range of forests and terrains on which to develop and train an accurate machine learning model. The ultimate goal of this project is to apply the model across Alaskan and even Canadian birch forests to find and track invasive birch leafminer infestations.

Getting accurate birch leafminer infestation maps into the hands of the people responsible for forest management and decision making is critical for mitigation efforts. Imagine what the Forest Service could do with the time and money saved if this project is proven successful?

References

FS-R10-FHP. (2008). Forest health conditions in Alaska 2007. U.S. Forest Service, Alaska Region. Publication R10-PR-45.

FS-R10-FHP. (2020). Forest health conditions in Alaska 2019. U.S. Forest Service, Alaska Region. Publication R10-PR-45.

Hall, R. J., Castilla, G., White, J. C., Cooke, B. J., & Skakun, R. S. (2016). Remote sensing of forest pest damage: A review and lessons learned from a Canadian perspective. The Canadian Entomologist, 148(S1), S296-S356.

Snyder, C., MacQuarrie, C. J., Zogas, K., Kruse, J. J., & Hard, J. (2007). Invasive species in the last frontier: distribution and phenology of birch leaf mining sawflies in Alaska. Journal of Forestry, 105(3), 113-119.